Bias-Variance Tradeoff

1. Definitions

- Bias:

- Error from erroneous assumptions in the learning algorithm.

- High bias causes underfitting (model misses relevant patterns in data).

- Variance:

- Error from sensitivity to small changes in the training set.

- High variance causes overfitting (model learns noise and fails on unseen data).

2. Goal of Model Selection

Choose a model that:

- Accurately captures patterns in training data.

- Generalizes well to unseen data.

Key Challenge: Balancing these goals is often contradictory.

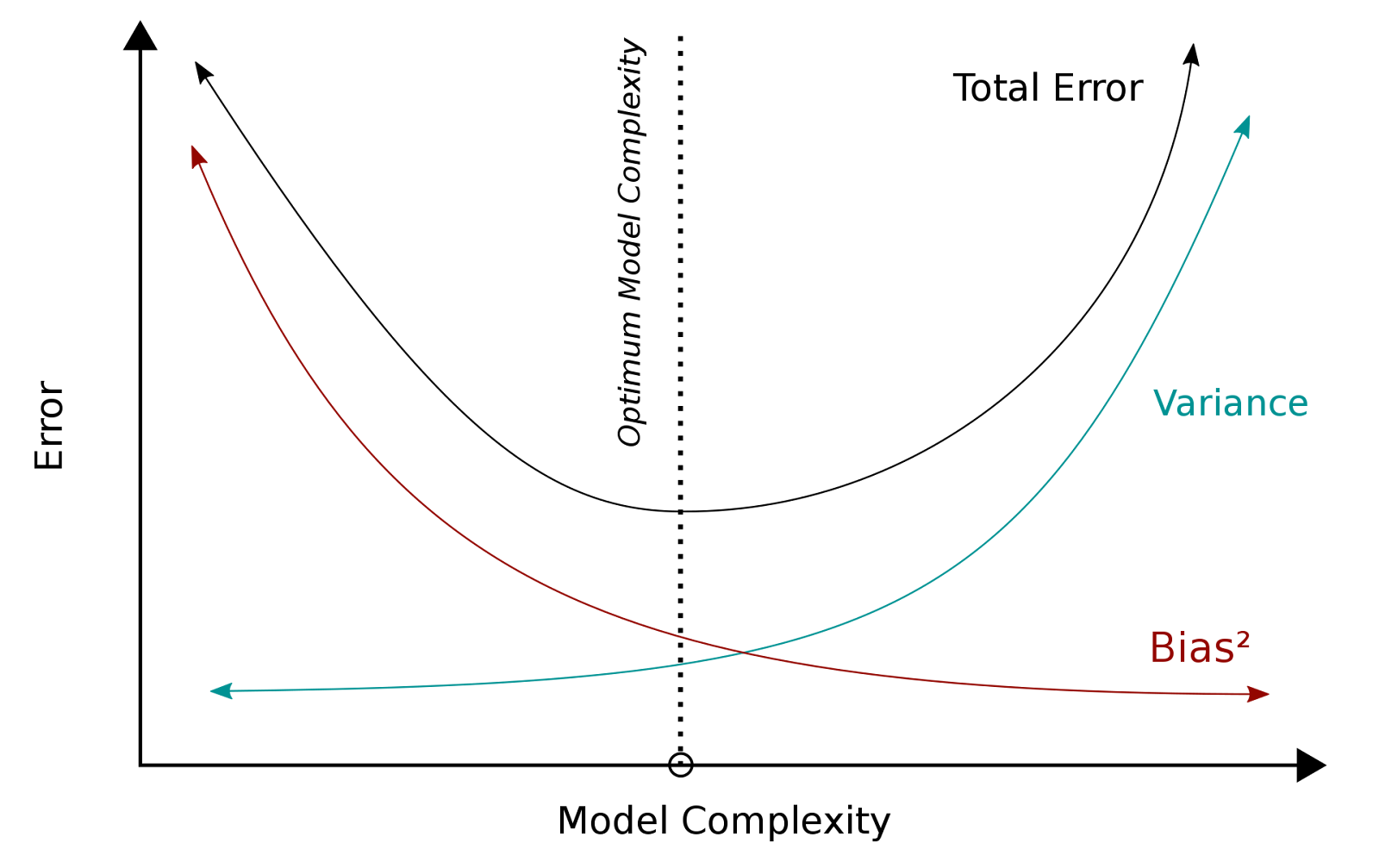

3. Tradeoff Dynamics

- High-Variance Models:

- Complex models (e.g., deep neural networks).

- Excel on training data but overfit to noise.

- Poor test performance.

- High-Bias Models:

- Simple models (e.g., linear regression).

- Underfit by missing key patterns.

- Consistent but inaccurate predictions.

4. Impact of Model Complexity

- Increased Complexity:

- Reduces bias (captures more patterns).

- Increases variance (sensitive to noise).

- Example: Flexible model \( \hat{f}(x) \) fits training data closely but overfits.

- Reduced Complexity:

- Increases bias (misses patterns).

- Reduces variance (stable predictions).

- Example: Rigid model ignores subtle relationships.

As model complexity increases, bias decreases but variance increases. The optimal balance minimizes total error.

5. Conclusion

- Underfitting: High bias, low variance (too simple).

- Overfitting: Low bias, high variance (too complex).

- Optimal Model: Balances bias and variance for minimal generalization error.

Mathematical Derivation of Bias-Variance Tradeoff

1. Mathematical Setup

Let \( Y \) be the target variable and \( X \) be the predictor variable:

\[ Y = f(X) + e \]

- \( e \) is the error term, normally distributed with \( \text{mean} = 0 \).

- We build a model \( \hat{f}(X) \) to approximate \( f(X) \).

2. Expected Squared Error Decomposition

The expected squared error at a point \( x \) is:

\[ \text{Err}(x) = E\left[ (Y - \hat{f}(x))^2 \right] \]

This error can be decomposed into three components:

\[ \text{Err}(x) = \underbrace{\left( E[\hat{f}(x)] - f(x) \right)^2}_{\text{Bias}^2} + \underbrace{E\left[ (\hat{f}(x) - E[\hat{f}(x)])^2 \right]}_{\text{Variance}} + \underbrace{\sigma_e^2}_{\text{Irreducible Error}} \]

3. Components of Error

- Bias²:

- Measures the difference between the expected model prediction \( E[\hat{f}(x)] \) and the true value \( f(x) \).

- Formula: \( \text{Bias} = E[\hat{f}(x)] - f(x) \).

- Variance:

- Measures the variability of model predictions around their mean.

- Formula: \( \text{Variance} = E\left[ (\hat{f}(x) - E[\hat{f}(x)])^2 \right] \).

- Irreducible Error:

- Error caused by noise (\( \sigma_e^2 \)) in the data.

- Cannot be reduced by improving the model.

4. Key Takeaways

- Bias: High bias indicates underfitting (model oversimplifies the true relationship).

- Variance: High variance indicates overfitting (model is too sensitive to noise).

- Irreducible Error: Represents the inherent noise in the data.