Support Vectors in SVM

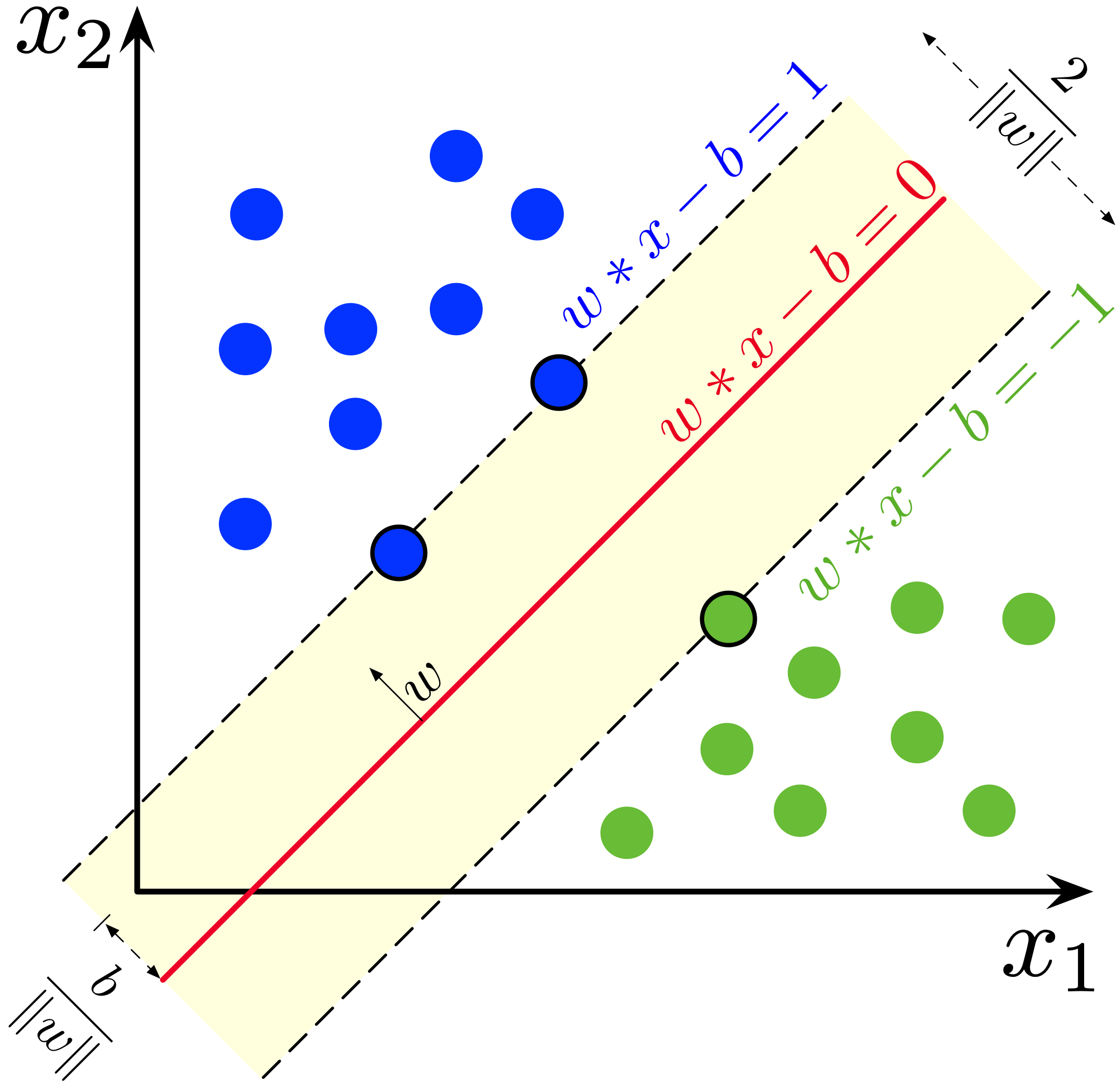

In Support Vector Machine (SVM), support vectors are the data points closest to the decision boundary (hyperplane). These points are crucial because they determine the position and orientation of the hyperplane and influence the margin between classes.

Mathematical Representation

The decision boundary in SVM is represented as:

w · x - b = 0

where:

- w is the weight vector (defines the orientation of the hyperplane).

- x is the feature vector.

- b is the bias term.

The support vectors satisfy:

w · xi - b = ±1

Visualization of Support Vectors

The diagram below represents the support vectors, the margin, and the decision boundary:

Key Properties of Support Vectors

- They define the optimal hyperplane – Support vectors are the critical data points that affect the placement of the decision boundary.

- They lie closest to the hyperplane – The margin is calculated based on the distance of these support vectors from the hyperplane.

- They help maximize the margin – SVM creates a hyperplane with the maximum margin, ensuring the decision boundary is as far as possible from the support vectors.

- Only support vectors influence the decision boundary – Other data points that are farther away do not contribute to defining the hyperplane.

Why Are Support Vectors Important?

- They make SVM robust – Even if non-support vector data points are removed, the model remains the same.

- They improve generalization – A well-defined margin ensures better performance on unseen data.

- They help in both linear and non-linear SVM – In non-linear SVM, a kernel function maps the data to a higher-dimensional space where it becomes linearly separable.